It had been a long day at VetCare, I think I had made it home for maybe 3 hours on my on-call Sunday, very unlike the typically relaxed Sundays following a busy Saturday. I had just been to the clinic to check on my epileptic emergency earlier in the day and while still agitated, there was no evidence of any more seizures and he seemed to be more under control. So far, so good. Our clinic motto (while a little optimistic and some days, possibly unrealistic) ‘No-one is gonna die on our watch’ had so far been fulfilled this weekend.

I had my obligatory unwind-before-bedtime tea and curled up into bed. It was 11.45pm. Tossing the days cases over in my head I started to drift off. 12.07am – the duty phone rang. I hadn’t been asleep long enough to be groggy, so I answered on the third ring. It was a 12 year old Weimaraner Rex, who was outside panting hard and unwilling to get up to go back inside. This was very unlike him. His family thought his abdomen seemed bloated and they were very worried. He had been fine earlier in the evening as he had gone for a walk at about 8pm and seemed completely himself……..Something had gone very wrong.

Teasing Rex’s symptoms apart in my head, I quickly knew he had to come in. His relieved family would meet me in the clinic in ~20mins. As I changed back into my work clothes, Dr Nick (he insisted I state he is my husband, in case there was any confusion of what he was doing here) stirred and asked groggily,

‘What have you got?’

‘A 12 year old Weimaraner with a GDV’ I replied.

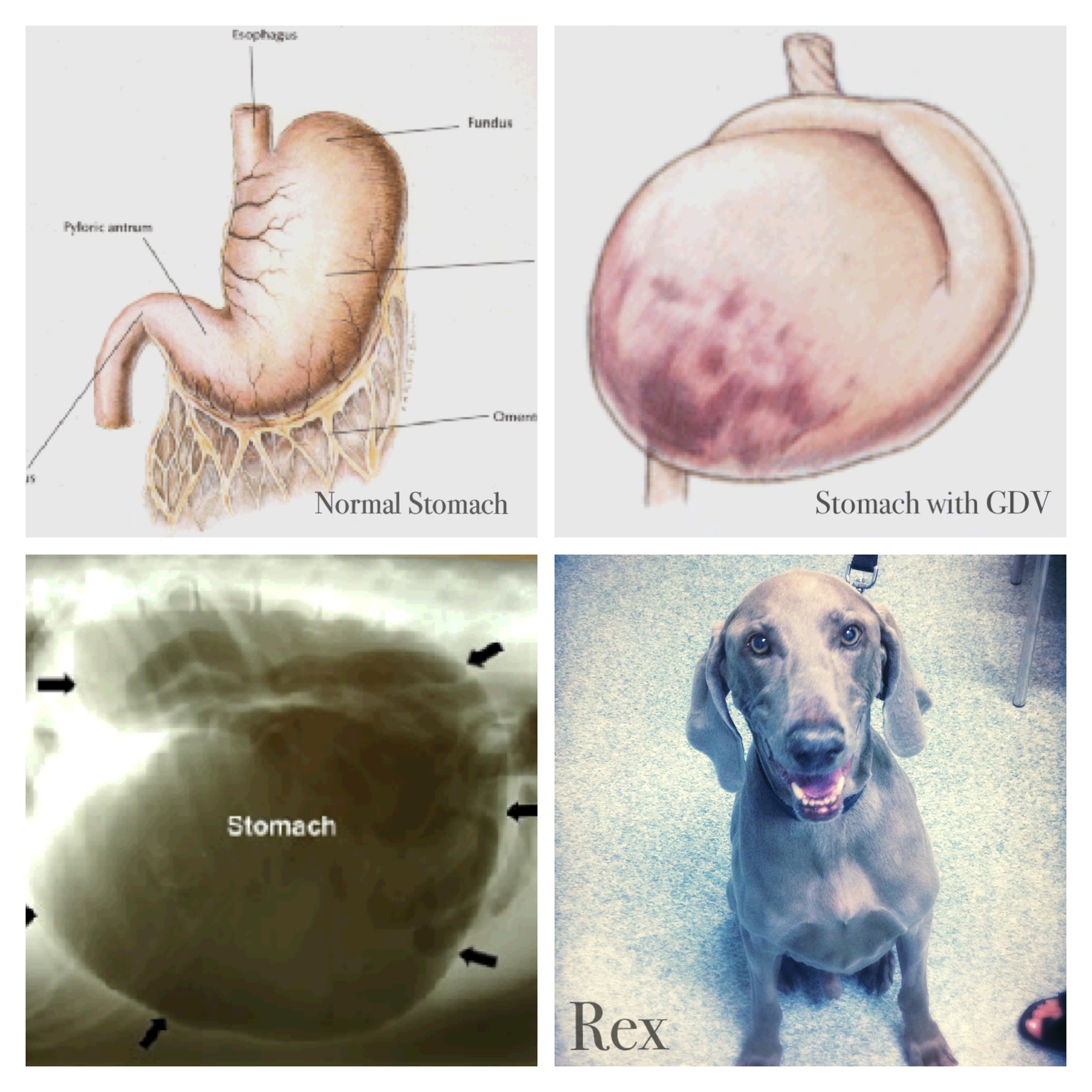

I was joking…….. But I was worried. A GDV stands for gastric dilation and volvulus. It is a syndrome where the stomach twists and bloats with gas build up blocking vital blood supply to organs and releasing toxins into the blood stream. It is more commonly found in deep chested dogs (breeds such as German shepherd, German Short Haired Pointer, Great Dane, Huntaways….Weimaraners) and apart from a hit by car case or maybe a splenic bleed, it was right up there as the emergency of all emergencies. Those that have read the book or seen the movie ‘Marley and Me’ will know just how much trouble Rex was in.

Dr Nick and I had attended a conference in Brisbane 2 years earlier where they considered the best chance of achieving success with a GDV case, surgical correction had to occur within 6 hours of the GDV occurring. The patient had to be stabilised with fluids, the gas bloated stomach decompressed, then surgically untwist and permanently fix the stomach to the side of the abdominal wall to prevent the stomach from twisting again in the future. After meeting Rex’s family, all distraught their beloved boy was in so much pain and discomfort, an X-ray was taken to confirm my suspicion. The xray image below shows a large, round darkly shadowed region inside the abdomen is a grossly enlarged, gas filled stomach. A stomach this size is not only painful, but dangerously compresses the organs surrounding it, cutting off vital blood circulation and pushes into the thoracic space causing difficulty breathing. A white line cuts through the round shape. This is called compartmentalisation and confirms the stomach is not only distended but is also twisting. I was very concerned about Rex’s condition. The success rate of GDV surgery can be as little as 45%. Rex had eaten dinner as per usual and gone for a walk at ~8pm and he had been normal then. It was now 12.45am and most likely a maximum 4.5 hours since the GDV had occurred. We were still well within the 6 hour window if we got surgery started as soon as possible and this increased our chances of success. I relayed the information to Rex’s family. There would be no guarantees. If they chose not to go ahead with surgery, they would have to say goodbye to Rex sooner rather than later. We have seen GDV cases in such excruciating pain they have lashed out and bitten, (even sending Dr Nick to hospital!) purely due to the agony they were in and no-one wanted to put Rex through that. After a family meeting, the brave decision was made to give Rex a chance and have the surgery. Once the decision was made, preparation for the long night ahead started immediately. It was a tricky surgery and I had already worked most of the day already. I knew the surgery would go smoother with two vets involved. So, I once again woke up Dr Nick, (and he still thought I was joking). Nick’s Dad Digby, now our honorary VetCare member, was called and he rolled up to our house with his sleeping bag to bunk down on our couch and hold down the fort (including two sleeping kids, three dogs and a cat!).

Whilst waiting for the others to arrive I set Rex up on IV fluids, antibiotics, additional pain relief and organised the anaesthetics he would need. Nurse Georgia arrived to finish helping with the vital IV fluids and whilst attending to this Dr Nick arrived and walked straight to the kettle to brew a coffee. I thought this was a little odd and maybe could be misconstrued as unprofessional but he advised me later it was going to be a long night and he would perform better with a coffee on board – enough said! Can’t argue with that! For us it was like preparing for a surgical marathon. Even though this is what we trained for, a GDV case may only occur in our practice once or twice a year. It’s not a case you see everyday and practice to get good at…. a lot could go wrong. The last of Rex’s family said their goodbyes, with good luck’s and ‘see you on the other side’ kisses. We made a plan to anaesthetise Rex, then attempt to decompress the bloated stomach before entering the abdomen. With septic shock, reduced thoracic capacity, cardiac arrhythmia and metabolic imbalances, GDV patients are high risk for anaesthesia. This could be a risky induction. We chose to use our regular induction agent, but only to effect not to Rex’s dose for weight. The drug was given IV and the ET tube was passed and connected to the oxygen and anaesthetic gas circuit. Georgia worked on securing it in place and getting the pulse oximeter working to read Rex’s stats. As I turned back to Rex after adjusting his oxygen flow, Rex took a gasp, his eyes dilated and he stopped breathing. I immediately started IPPV, a technique to breath for Rex as his colour darkened a dangerous purple colour and yelled out to Nick to help. He dropped his coffee (literally!) and rushed over to check Rex’s heart.

‘He’s still here, …..we’ve got him!’

We knew this wasn’t a good start. In some critical cases a nurse would have to breath for an unstable patient throughout a surgery. If Rex remained unstable we would need an extra nurse. Georgia got the pulse oximeter onto Rex. His heart was steady and strong, but his oxygenation was a low reading of 84%. The surgical ideal would be for Rex’s oxygen to be over 94% to provide necessary oxygen to all organs, in particular Rex’s brain. Within one minute it was clear Rex was slowly starting to take his own breaths. Within another minute Rex’s stats were up to 90% and he was steadily breathing….another minute and the stats were up to 96%. We all knew we had dodged the first bullet of the night but we had to move quickly and steadily as we had a lot of work ahead of us. VetCare is well prepared for emergencies such as these and a stomach tube to decompress GDV’s is kept under the sink. We measured a rough estimate of how far it had to go to pass into the stomach while Georgia started to clip and prep a large abdominal surgical site. We lubed up the end of the tube and passed it deeper and deeper into Rex’s mouth, into the oesophagus to the entry to the stomach. More often than not with GDV’s (particularly if they had occurred past the 6 hour mark) the stomach was so twisted the oesophagus would be twisted closed and this technique of decompressing the stomach would fail. I felt a pop as I placed gentle pressure onto the tube. There is a risk if too rough with the tube the oesophagus could be torn……..It felt like a release, not a tear. Almost instantly a small surge of fluid poured from the tube into the bucket below. It had a fetid acidic smell, like vomit. We were in the right place! This was the next hurdle we just crossed, but nothing more came. The stomach wasn’t decompressing with the small amount of fluid that passed. The tube had blocked with the stomach contents…..most likely Rex’s dinner that night. We tried and tried again to unblock to tube and repass it, but it became clear even though the tube was passing, we weren’t going to get the result of decompression we wanted.

Plan B: (always good to have one as a vet!) Decompress the stomach by using a large gauge needle through the skin into a hollow has filled pocket in the stomach.

‘Is it working?’

We couldn’t see any major change in the size of the grossly ballooned abdomen in front of us. Dr Nick floated his finger over the pink base of the needle,

‘I think I can feel it!’

The stench eventually made its way to our nostrils….. It was clearly working but only very slowly. It did release a fair amount of pressure off the stomach, returning blood flow to vital organs but we still had a long way to getting this stomach to a normal size. We scrubbed and entered the abdomen. On making the cut through the linea alba, the omentum was the first layer to be seen. This gives the first clue to which way, (anti- clockwise or clockwise) the stomach was twisted and which way to reverse the twist to put the stomach back into place. The stomach was still too large to turn so we again decompressed with another needle intra – operatively and waited. Again we tried to pass the stomach tube but again it was clogged with food. In some cases, the stomach is entered and the contents removed but it adds to the risk of post operative infection and we chose not to add to Rex’s problems considering it should have been his regular diet in his stomach rather than him stealing rubbish or eating things he shouldn’t have. After our slow attempts, we finally had the stomach to about a third the size it had been. Now smaller, it was easier to rotate into the proper position. The stomach wasn’t the only thing to be concerned about. Sometimes the spleen would be involved in the twisting with the stomach and need removing. Attached to the spleen was a series of small blood vessels that can also rupture with the twisting, causing life threatening haemorrhage. While Rex’s spleen looked normal, there was a large pool of blood in the abdomen suggesting these and possibly other vessels had been ruptured. Rex’s colour remained pink and his stats on the pulse oximeter were as stable as any routine surgery. We used lap sponges to mop up the blood to check the rest of Rex’s organs. There didn’t appear to be any necrotic tissue needing removal, caused by lack of blood supply. The bleeding had slowed to a small ooze, so the spleen was left in place. Now the stomach was in place and the organs looked ok our job was to fix the stomach to the inside of the abdominal wall to prevent recurrence of the GDV. While there are a list of techniques possible to do this, the Brisbane conference had stated the simple linear incisional pexy was in the top two techniques recommended. This basically involved placing a single incision into the serosal (uppermost) surface of the stomach and into the first muscle layer of the abdominal wall and suturing the raw edges together. It came together nicely. After a quick flushing clean of the abdomen and a further check the bleeding was under control we closed Rex’s abdomen and hoped what we had done would be enough for Rex to make a full recovery. We knew even though the surgery had gone well and everything ‘looked’ ok, there was still a range of life threatening post operative complications that could happen. He would need careful monitoring and extra care in our hospital over the next few days.

I made the call to Rex’s worried family. It was now 5 am. After a long day, I had worked all night. Dr Nick made his way home to relieve his Dad and I followed after a full hand over of Rex to the VetCare team that had arrived for the day. We ensured Rex had woken from anaesthesia, was monitored regularly and was in stable condition. I climbed back into bed just after 6am. Our son flicked the light on again at 7.30am and our regular Monday morning was off to its normal start. Dr Nick got to drink that coffee he had been needing and I was off to school to drop our school boy off and spend the rest of the day with little Pia.

A day later Digby had popped into the clinic, I proudly showed him the dog he ‘helped’ save. Rex was now up on his feet, looking bright and was anxious to get home. The last hurdle was to get him eating but typical of the odd highly strung Weimaraner dogs he was refusing any food we put in front of him. We all agreed he needed one more night of hospital care on IV fluids but if all going well, he could go home on good behaviour Tues night to see if he would eat at home. His family could always drop him back to the hospital in the morning if needed. In some cases, where the patient still refused food they would have to get their nutrition through a nasogastric tube, (we were hoping to avoid this). Rex continued to do well and was discharged into the care of his family. To the relief of us all he hungrily ate the small portions of a prescription food provided. Rex continued to go from strength to strength. He is pictured here smiling after having his sutures removed ten days after surgery. What a handsome lad and what a fantastic recovery for a 12 year old. He was a wonderful, brave patient and we wish him the very best!

Risk Factors associated with Gastric Dilation and Volvulus:

- Deep Chested dog breeds such as Great Dane, German Short Haired Pointer, Weimaraner,

- Fed one meal a day

- Fed and then exercised

- Older dogs 6yrs – 12 years

- Anxiety

- Having water before and after a biscuit meal

- Family history for GDV

- Elevated bowl

Factors that reduce the chance of your dog getting a GDV:

- Feed two smaller meals per day

- Not exercising immediately after eating

- Smaller kibble size

- Good quality dry food with a meat protein high in calcium

- Calmer Temperament